Mike Rose has been with Morris and James from its very early days, helping establish and then take the business from its artisan origins to a pottery that successfully balances art and industry. Mikes background in chemistry and early involvement in the ceramics industry provided the technical platform which has enabled the pottery to use sometimes less than ideal materials, equipment and facilities. Over the years he has become expert in coaxing the best from our local clay and adept in providing an ever increasing range of colours for our decorators to work with.

He reflects on the changes he has seen during that time:

“Having just completed 30 years as technical manager of Morris and James Ltd, I decided to write a brief account of production process development at the pottery. The social and economic history of the company is well covered in the book “The Mud and Colour Man” but that publication, intended for a general readership, is light on technical details. I hope this goes some way to completing the picture.

When Anthony and Sue Morris purchased a malodorous run-down Matakana piggery in 1977 with a view to establishing a craft pottery on the site, it is tempting to assume they had a vision of “Morris and James” as it now appears nearly forty years on. This, however, is far from the truth since Morris and James has reinvented itself many times in the intervening period.

It began as a typical 1970’s craft pottery, with Anthony making all the products from unglazed terracotta assisted by a local teenager to do the labouring, and Sue in charge of marketing and accounts. Anthony’s throwing wheel was an original Victorian cone drum wheel converted from steam power to electricity and is now on display in our showroom. Our current throwing wheels are driven by hydraulic motors.

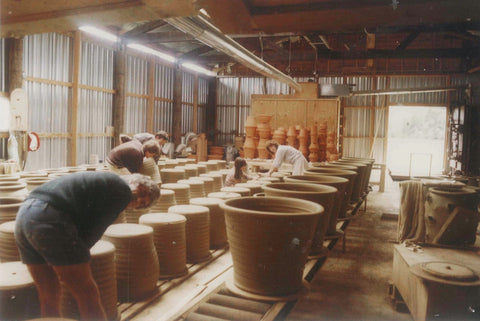

The first step along the road to becoming a small manufacturer was the introduction of slop-moulded floor tiles to the product range. This necessitated recruiting additional employees and began the process of expansion. At this time, Anthony would load the pots he had made into his ute, drive them to Auckland, and hawk them around the garden centres. On one occasion, he had some large pots which particularly appealed to a garden centre owner who promised to buy all Anthony could produce. Anthony soon realized that machinery would be needed to make these pots in quantity. After several attempts to improvise suitable machines, he eventually purchased a second-hand vertical extruder in Australia and began the long process of working out how to form pots by hand-throwing, but starting from an extruded cylinder.

The problem of preparing sufficient clay for the increased production proved to be particularly intractable. The fire destroyed the original ribbon mixer, but in any case this machine would have been far too small. Over the next five years, four completely different processes were tried before a suitable method was found, entailing considerable expenditure on machinery and using up countless hours of work. A filter press was shipped out from England, but Matakana clay proved to be too fine and sticky for this method to work. (The filter press was sold to potter Royce McGlashan in Nelson, for whom it worked brilliantly). Next, a pan mill was purchased, but pan mills need a constant, controlled feed of raw materials and this one did not take kindly to being fed from a front end loader. The next idea was to use a hammer mill to reduce dry clay to a powder, then after blending with a filler, reconstituting it with water in a trough mixer. This was reasonably successful, but high maintenance costs made it uneconomic. Lack of prepared clay was a constant restriction on production. Finally, a retired quarry-man suggested we rotary-hoe the clay in the paddock and sieve it to a suitable particle size. This is basically the method we still use, but we have since added two sets of smooth rolls to improve the process.

When Roger Douglas ended New Zealand’s siege economy in the mid 1980’s, manufacturing became less financially attractive and importing became more so. Morris and James’ response to this was to open retail stores in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch, to sell products made in Matakana but also imported goods. We had begun producing glazed pots in strong, bright colours and these were selling well. Floor tiles were a major component of our product mix, but not the original slop moulded ones. After the fire, the process was changed to hand moulding from extruded blanks. The intention was to increase capacity and improve technical quality. A new kiln and dryer were built, but drying and firing the new tiles proved to be far more difficult than anticipated. Tiles from overseas were imported to broaden the range. Eventually, so many tiles were being imported by other companies that Morris and James found they could not compete and the manufacture of floor tiles was discontinued.

The cost of setting up and stocking a retail operation, together with expenditure on new machinery, was financed with large bank loans. Sales were insufficient to service the debt, and in 1990 the company was placed in receivership. Thanks to an enlightened Official Receiver the company traded out, but the staffing level in the factory was reduced from 35 to 12 (it is now 22) and retailing in the major centres ended.

In 1993, some two years after coming out of receivership, the company had an unexpected piece of good fortune. A company named Brewsters, specializing in hiring out pot plants, wanted some glazed terracotta planters to be made to their own design, for supplying to their corporate clients. The initial order was for about one hundred pots over three months, but they were so popular that the order was extended. Our association eventually lasted for seven years and many thousand Brewsters pots were produced. In order to produce pots at the required rate, an upgrade in facilities was essential – and fortunately the steady income made this affordable. Previously, the drying of the pots was subject to only the most rudimentary control – achieved by either opening or closing large shutters to the outside elements.

Consequently the pots would dry too fast and crack or too slowly in which case we ran out of space. An enclosed, insulated drying room was now constructed in which the temperature and humidity could be controlled. This was popularly known as the “Summer Room”. A sophisticated pre-fabricated kiln car setting was ordered from England to increase our kiln car capacity for large pots. The construction of a large new building allowed an expansion of the spray glazing operation. Our crude galvanized iron spray booths were replaced with better-designed fibreglass ones, and a facility for cleaning and recycling the wash down water was constructed.

One of our challenges, over the years, has been the fact that both the vertical extrusion-based making method and Matakana clay are more suitable for large items. We also need smaller items in our product range, so it is necessary to have other production processes that dovetail with the large ware production. Our popular blue and white kitchenware was designed by Anthony in the late 1980’s. It was made by using the vertical extruder to form flat sheets which were then shaped by drape moulding. The clay was a special blend produced in Dunedin by a friend of Anthony. At one stage we were supplying hundreds of pieces to a design shop in Auckland. Production was scaled back when that shop went out of business. The special clay became unavailable some years ago, but we continue to make small quantities of kitchenware with alternative material.

Slip casting is a common process for making small items, but it works much better with white clays than red. We have done many experiments over the years with slip casting, and we once produced a range of slip cast bowls designed by Anthony’s son Patrick. However we decided that the dangers of contamination meant that it was unwise to have both white and red clay bodies being processed at the same premises. An Auckland company with which we have a long association supplies us with slip cast tableware in the biscuit state which we then decorate with our own distinctive glazes.

The “jigger/jolley” process is also frequently used for making tableware. In the mid 1990’s we had plans to develop a jigger/jollied range of products, but the only success was a coffee mug glazed to match the kitchen ware. Last year (hopefully learning from our experience twenty years ago) we have started to develop this process again”.

- Nick C

GLOSSARY

DRAPE MOULDING: A forming method where a flat sheet of clay is draped over an upside down mould. Our moulds were made from oiled wood.

FILTER PRESS: A machine used to de- water clay after it has been wet-sieved. The clay slurry is pumped under pressure through nylon filter cloths supported on metal frames.

HAMMER MILL: A mill containing rapidly rotating hammers within a metal casing.

JIGGER/JOLLEY: A forming method in which a metal tool forces clay against the inside of a rotating plaster mould.

PAN MILL: More correctly called an “edge runner mill.” The version used at Morris & James included a rotating shallow pan. Two heavy circular mullers mounted on a horizontal axle forced the clay through perforations in the bottom of the pan.

RIBBON MIXER: A type of trough mixer where the mixing action is performed by a thin steel blade formed into a spiral.

SLIP CASTING: A forming method where chemicals are used to increase the fluidity of a mixture of clay and water. The resulting “slip” is then poured into plaster moulds.

SLOP MOULDING: A forming method where clay is made up into a paste with water and then pushed into wooden moulds.

TROUGH MIXER: Also called a “double shaft mixer”. A trough has two horizontal shafts passing along it. Inclined paddles attached to the shafts simultaneously knead the clay and push it from one end to the other, where it is discharged.

TRUCK KILN: A kiln in which the floor of the hot zone consists of a removable deck on wheels. The combination of deck, steel chassis, wheels and kiln furniture is called a “kiln car”. The kiln cars run on rails through the factory, so that loading and unloading can be done in locations remote from the kiln itself.

VERTICAL EXTRUDER: A machine primarily used to form clay pipes. Clay is forced vertically downwards through a ring-shaped die.